Page 30, Paragraph 3:

"What did Hob's son think about this?" I say. She moves her neck and arms, to show she doesn't know. She says, "It doesn't matter what Hob's son thinks about it - there's no good in it for him. If he runs away from the village he won't have anything to eat, and won't survive very long. If he doesn't run, Hob will kill him. Hob's son may do one thing or the other, but neither one nor the other is good for him."

Paragraph 4:

She puts up her arms to stretch her back. Her little breasts push their shape against her clothing. Now she stands up and says to me, "Come on, so we can walk farther along the river's edge." She puts out her hand to pull me up so that I'm standing. Her hand is sweaty.

Paragraph 5:

We walk by the river now and say nothing; we walk through a hill of dead leaves that comes up to our knees, and by walking through them scatter them everywhere. We walk underneath the trees, where we see the bridge aways off. The bridge looks bigger in the sunlight than it did in the dark - I tell the girl this. She stops, and turns to look at me.

Wednesday, September 30, 2009

Tuesday, September 29, 2009

Page 29, Paragraph 6 - 8; Page 30, Paragraphs 1 and 2; Notes

In which we get TMI regarding our narrator's snacking habits.

***

Page 29, Paragraph 6:

Across the water a bunch of ducks rise up loudly and fly aways off above the wetness and the water, in the direction of the valley's edge. A caterpillar falls on my foot - the furry kind. I pick it up between my fingers now and pull, so that I tear it to pieces, and I play with it for a long time like this, and lick it* from my hand. The girl turns away from the river now to look at me. "It's the nomadic people that put their sons to the axe," she says.

Paragraph 7:

"No," I say. "Beasts and birds don't either, unless they're crazy. I've never heard anything as frightening or strange as this before. Why, I can't think of anything worse than putting children to the axe." I go on like this, and [then] say, "Didn't Hob like** his son? Otherwise, how could he do that to him?"

Paragraph 8:

"That isn't it," says the girl. "That isn't it at all. Hob loves and wants his son more than a man loves and wants his mate. More than the fire loves the dry tree. He doesn't want to kill his son."

Page 30, Paragraph 1:

I say, "But Hob can say 'no' to this, and say he's not going to kill his son, because his in charge of a lot of people."

Paragraph 2:

"People want the path," she says. "People want skins and meats, and the good times that having the path come by them will bring. The settlers have gotten food and clothing and so forth for Hob for a long time, and now they want him to make a path for them, as is their due. If he doesn't kill his son and make the path right, he won't be in charge of them anymore. If he doesn't do right by them, why, they'll want to make him and his son go away from here. Cast them out, and make them forage, which might be the death of them."

*The caterpillar goo, presumably

**I think our narrator uses the same word for "like" and "love"

***

Page 29, Paragraph 6:

Across the water a bunch of ducks rise up loudly and fly aways off above the wetness and the water, in the direction of the valley's edge. A caterpillar falls on my foot - the furry kind. I pick it up between my fingers now and pull, so that I tear it to pieces, and I play with it for a long time like this, and lick it* from my hand. The girl turns away from the river now to look at me. "It's the nomadic people that put their sons to the axe," she says.

Paragraph 7:

"No," I say. "Beasts and birds don't either, unless they're crazy. I've never heard anything as frightening or strange as this before. Why, I can't think of anything worse than putting children to the axe." I go on like this, and [then] say, "Didn't Hob like** his son? Otherwise, how could he do that to him?"

Paragraph 8:

"That isn't it," says the girl. "That isn't it at all. Hob loves and wants his son more than a man loves and wants his mate. More than the fire loves the dry tree. He doesn't want to kill his son."

Page 30, Paragraph 1:

I say, "But Hob can say 'no' to this, and say he's not going to kill his son, because his in charge of a lot of people."

Paragraph 2:

"People want the path," she says. "People want skins and meats, and the good times that having the path come by them will bring. The settlers have gotten food and clothing and so forth for Hob for a long time, and now they want him to make a path for them, as is their due. If he doesn't kill his son and make the path right, he won't be in charge of them anymore. If he doesn't do right by them, why, they'll want to make him and his son go away from here. Cast them out, and make them forage, which might be the death of them."

*The caterpillar goo, presumably

**I think our narrator uses the same word for "like" and "love"

Monday, September 28, 2009

Page 29, Paragraphs 2 - 5; Notes

Page 29, Paragraph 2:

Now she talks about the antler-headed men, and of their spell.* "The spell is a creation stranger and bigger than anything ever made in the world before, bigger than the circle of standing stones that people have made on a big field, far in the east.** She says, "To create this spell, the antler-headed men need a power and a strangeness of thought that they haven't had before. A power that comes from the other world, beneath the earth, where the spirits walk."

Paragraph 3:

"Hob and his stick-headed kind take this power from the spirit world," the girl says, "and the spirits, likewise, take their due from the antler-headed men." Now she is quiet. "How do the spirits take their due?" I say.

Paragraph 4:

She explains how the spirits take that which the antler-headed men want more than anything else in the world, whatever that may be. This thing is put to the axe by the antler-headed men - killed - and is then taken by the spirits down to the other world. As is due for this, the spirits give power to the antler-headed man, and strangeness in his thoughts, so that he may cast the spell correctly.

Paragraph 5:

"And with Hob," I say, "what's this thing that he wants more than anything in the world, which the spirits make him put to the axe?" Now she takes her foot from the river, white and cold, with little beads of water standing out on it. "It's his son," she says. "It's his son."

*I'm not really sure how I want to translate "saying-path" here - I'm going to go with "spell" for now, for reasons that should become apparent as we go along.

**Stonehenge!

Now she talks about the antler-headed men, and of their spell.* "The spell is a creation stranger and bigger than anything ever made in the world before, bigger than the circle of standing stones that people have made on a big field, far in the east.** She says, "To create this spell, the antler-headed men need a power and a strangeness of thought that they haven't had before. A power that comes from the other world, beneath the earth, where the spirits walk."

Paragraph 3:

"Hob and his stick-headed kind take this power from the spirit world," the girl says, "and the spirits, likewise, take their due from the antler-headed men." Now she is quiet. "How do the spirits take their due?" I say.

Paragraph 4:

She explains how the spirits take that which the antler-headed men want more than anything else in the world, whatever that may be. This thing is put to the axe by the antler-headed men - killed - and is then taken by the spirits down to the other world. As is due for this, the spirits give power to the antler-headed man, and strangeness in his thoughts, so that he may cast the spell correctly.

Paragraph 5:

"And with Hob," I say, "what's this thing that he wants more than anything in the world, which the spirits make him put to the axe?" Now she takes her foot from the river, white and cold, with little beads of water standing out on it. "It's his son," she says. "It's his son."

*I'm not really sure how I want to translate "saying-path" here - I'm going to go with "spell" for now, for reasons that should become apparent as we go along.

**Stonehenge!

Tuesday, September 22, 2009

Off-Topic: Heretofore Unknown Comedian-Joker-Eno-Blake Connection Revealed!

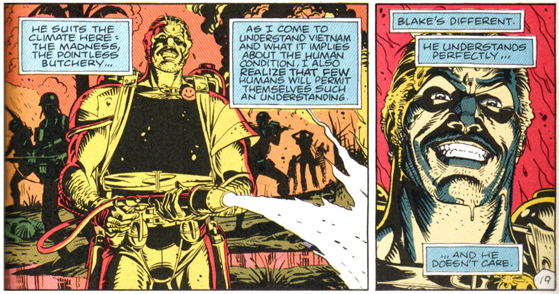

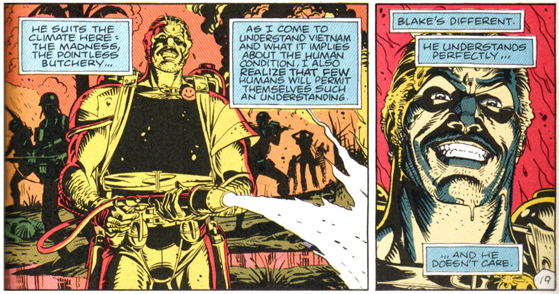

Something I've done a lot since starting this blog (in addition to looking up information about life on the British Isles during the Stone Age, reading about a million Alan Moore interviews on the net, et cetera) is flip through my collection of Alan Moore trade paperbacks, looking for ways in which his comics work connects (thematically, stylistically, or otherwise) with his writing in Voice of the Fire. I was doing this with my battered and re-re-re-read copy of Watchmen and started looking through the "Fearful Symmetry" chapter, which, IMO, still stands as the most amazing display of formal virtuosity in the history of the comics medium (no, I haven't read

Promethea yet). My eyes wander to the 6th and 7th panels of page 22 (I'm afraid you'll have to follow along in your own copies at home, folks - our scanner is presently covered under a small mountain of paper), in which the one cop is looking into the Comedian's file. I notice the number on the file: 801108, which, as Doug Atkinson points out in his excellent annotations, is a "palindromic number, and all the numbers in it have vertical and horizontal mirror symmetry," in keeping with the chapter's theme of symmetry and mirroring.

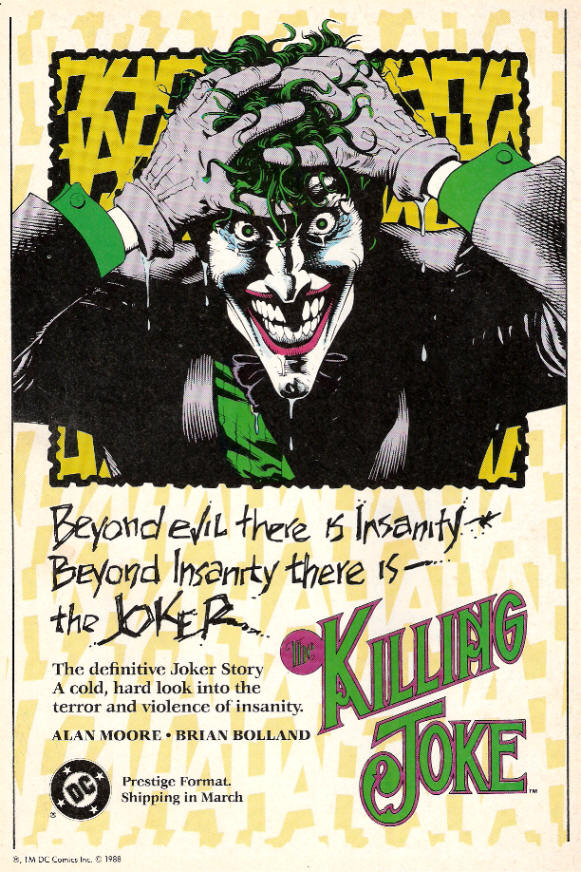

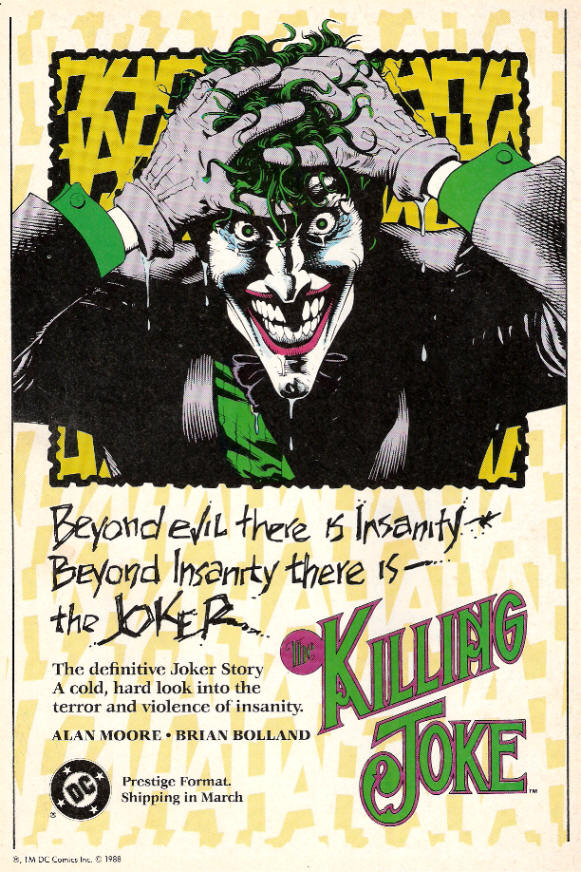

Then, following a weird hunch that I had, I picked up my copy of DC Universe: The Stories Of Alan Moore (still my favorite collection of Moore comics, aside from the Watchmen TPB) and turned to the page in The Killing Joke where Batman is walking in Arkham Asylum in the cell block where Two-Face and the Joker are held. I look at the number on Two-Face's cell - 0751. Hm - no help there. I look at the number on the Joker's cell - 0801. A-ha! Aside from the amusing link with the Comedian (a comedian is a joker - geddit?), I figure there's some significance to the number 801 besides that and the mirror symmetry thing. (Are you with me so far?). So I Google 801 and I'm reminded that 801 is a band that the musician Brian Eno was in back in the 70s. Why is this significant? Well, Alan Moore is a huge fan of Eno's, to the extent of naming a Swamp Thing story that he wrote, "Another Green World" after an Eno song of the same name. Wait! It gets better! The name 801 comes from a lyric in a song called "The True Wheel" from the album Taking Tiger Mountain (By Strategy). The name of the chapter in which we see the Comedian's file, "Fearful Symmetry", is taken from a poem called "The Tyger" by William Blake. And what's the Comedian's real name?

Why, Edward Blake, of course.

Who but Alan Moore could take us from an comics anti-hero to a super-villain to a groundbreaking ambient musician to a visionary poet and then back to the anti-hero?

The Comedian in Watchmen. Art by Dave Gibbons

Ad for Batman: The Killing Joke. Art by Brian Bolland

William Blake by Thomas Phillips (Wow! He's huge!)

Promethea yet). My eyes wander to the 6th and 7th panels of page 22 (I'm afraid you'll have to follow along in your own copies at home, folks - our scanner is presently covered under a small mountain of paper), in which the one cop is looking into the Comedian's file. I notice the number on the file: 801108, which, as Doug Atkinson points out in his excellent annotations, is a "palindromic number, and all the numbers in it have vertical and horizontal mirror symmetry," in keeping with the chapter's theme of symmetry and mirroring.

Then, following a weird hunch that I had, I picked up my copy of DC Universe: The Stories Of Alan Moore (still my favorite collection of Moore comics, aside from the Watchmen TPB) and turned to the page in The Killing Joke where Batman is walking in Arkham Asylum in the cell block where Two-Face and the Joker are held. I look at the number on Two-Face's cell - 0751. Hm - no help there. I look at the number on the Joker's cell - 0801. A-ha! Aside from the amusing link with the Comedian (a comedian is a joker - geddit?), I figure there's some significance to the number 801 besides that and the mirror symmetry thing. (Are you with me so far?). So I Google 801 and I'm reminded that 801 is a band that the musician Brian Eno was in back in the 70s. Why is this significant? Well, Alan Moore is a huge fan of Eno's, to the extent of naming a Swamp Thing story that he wrote, "Another Green World" after an Eno song of the same name. Wait! It gets better! The name 801 comes from a lyric in a song called "The True Wheel" from the album Taking Tiger Mountain (By Strategy). The name of the chapter in which we see the Comedian's file, "Fearful Symmetry", is taken from a poem called "The Tyger" by William Blake. And what's the Comedian's real name?

Why, Edward Blake, of course.

Who but Alan Moore could take us from an comics anti-hero to a super-villain to a groundbreaking ambient musician to a visionary poet and then back to the anti-hero?

The Comedian in Watchmen. Art by Dave Gibbons

Ad for Batman: The Killing Joke. Art by Brian Bolland

William Blake by Thomas Phillips (Wow! He's huge!)

Labels:

comics,

images,

links,

music,

off-topic,

other authors,

the internets,

video

Page 28, Paragraph 7 and 8; Page 29, Paragraph 1

I keep thinking this is gonna go into a scene from that one movie with Dennis Hopper in it.

***

Page 28, Paragraph 7:

Now she stands up and turns to me. She says, "Come on - put on those clothes so we can walk by the river's edge." I stand up and do as she says; I put the clothes on my legs, my belly and my back, and on my feet. They feel strange.

Paragraph 8:

From the pigpen we go by the hut, where the pile of firewood is that stands bigger than me. We come off the rise and by the reeds to the river's edge, where I came to take a piss before. We walk by the river there. I say to her, "You were telling me about the antler-headed men and the big path-saying, but you didn't say what this has to do with Hob's son or how he went away."

Page 29, Paragraph 1:

She says, "If you sit with me beneath the trees by the river's edge, I'll tell you everything there." And now we find the tree and sit here on the grass; she sits with her foot hanging down and her toes in the water, which makes bright rings.

***

Page 28, Paragraph 7:

Now she stands up and turns to me. She says, "Come on - put on those clothes so we can walk by the river's edge." I stand up and do as she says; I put the clothes on my legs, my belly and my back, and on my feet. They feel strange.

Paragraph 8:

From the pigpen we go by the hut, where the pile of firewood is that stands bigger than me. We come off the rise and by the reeds to the river's edge, where I came to take a piss before. We walk by the river there. I say to her, "You were telling me about the antler-headed men and the big path-saying, but you didn't say what this has to do with Hob's son or how he went away."

Page 29, Paragraph 1:

She says, "If you sit with me beneath the trees by the river's edge, I'll tell you everything there." And now we find the tree and sit here on the grass; she sits with her foot hanging down and her toes in the water, which makes bright rings.

Labels:

links,

notes,

page 28,

page 29,

random cinema reference

Sunday, September 20, 2009

Page 28, Paragraphs 2 - 6; Note

Page 28, Paragraph 2 (first paragraph after the break):

Flowers. Dawn. The girl says, "Come - Hob has gone off to the village down the river. Come on, sit up," and so forth. She takes me by my ratty hair and pulls a little. "Come now," she says. "I have food for you." Now I open my eyes and sit up.

Paragraph 3:

Ah, it's good that I didn't cross the bridge last night, and see no more of her. She's sitting by me with the sunlight on her, with skin whiter than the strip of aurochs hide wrapped around her hair. She's holding some bread in one hand and pears in the other.

Paragraph 4:

The pears are soft and good to eat; their juice runs down my chin. She smiles at this, and says she's found something else for me that's not food. Now I look and see clothing by her. There are pants, shirts, and moccasins.* "How did you come by those clothes?", I say, and as I'm saying this I spit a little piece of pear onto her hand. Now she lifts up her hand, sticks out her tongue, and licks it off, looking at me the whole time. A prickling comes in my penis.

Paragraph 5:

"The clothes are Hob's son's," she says, and says nothing more about it. She looks by the river, bright in the sun, and squints. I say, "How could Hob's son leave and not take his clothes?"

Paragraph 6:

She still looks at the river. She says, "He didn't need clothes where he was going."

*Or the Neolithic equivalents thereof

Flowers. Dawn. The girl says, "Come - Hob has gone off to the village down the river. Come on, sit up," and so forth. She takes me by my ratty hair and pulls a little. "Come now," she says. "I have food for you." Now I open my eyes and sit up.

Paragraph 3:

Ah, it's good that I didn't cross the bridge last night, and see no more of her. She's sitting by me with the sunlight on her, with skin whiter than the strip of aurochs hide wrapped around her hair. She's holding some bread in one hand and pears in the other.

Paragraph 4:

The pears are soft and good to eat; their juice runs down my chin. She smiles at this, and says she's found something else for me that's not food. Now I look and see clothing by her. There are pants, shirts, and moccasins.* "How did you come by those clothes?", I say, and as I'm saying this I spit a little piece of pear onto her hand. Now she lifts up her hand, sticks out her tongue, and licks it off, looking at me the whole time. A prickling comes in my penis.

Paragraph 5:

"The clothes are Hob's son's," she says, and says nothing more about it. She looks by the river, bright in the sun, and squints. I say, "How could Hob's son leave and not take his clothes?"

Paragraph 6:

She still looks at the river. She says, "He didn't need clothes where he was going."

*Or the Neolithic equivalents thereof

Friday, September 18, 2009

Page 27, Paragraphs 4 - 6; Page 28, Paragraph 1

Page 27, Paragraph 4:

Now I come alongside the river and through the trees, where I now see, a ways off in front of me, the river bridge I saw from the valley's edge. It's so big, and it's all made of wood - now I understand how it is that there are so many stumps nearby. The bridge lies on top of a lot of river huts like beavers make, and the noise of the river becomes loud below it. On the other edge, across the river, I see a path go a ways off, all bright in the white light of the moon.

Paragraph 5:

I have an urge. I have an urge to walk across the bridge, to leave by the moon-white path from the valley and return here no more. My mother didn't raise me to do strange things like sit by huts with antler-headed men and girls that smell like flowers. I'm one of the nomadic people, and am made for walking. I want to rise up out of this valley, where everything's wet and rotten-smelling. A village by the river, where the shagfoal walk. There's no good in it.

Paragraph 6:

Yet I think now of a lot of things. If I walk all alone and don't find anything to eat, I'll go hungry, like before I came to the white-skin hut. I think of the girl, with the strip of ox-fur holding back her long bright hair, and the smell of flowers all around her and the many good things she says. I think about Hob's son, whom I want to hear about, and now I look at the bridge and the white path across it, and hear the loud noise of the river, falling there in the dark.

Page 28, Paragraph 1 (first full paragraph):

I take a piss against the tree, and turn, and go back by the river's edge, and through the reeds, up the dirt rise and around the white skin hut, where I come by the pigpen. I crawl in the branch hut and beneath the hay. I shut my eyes, so that all of the world goes from me.

Now I come alongside the river and through the trees, where I now see, a ways off in front of me, the river bridge I saw from the valley's edge. It's so big, and it's all made of wood - now I understand how it is that there are so many stumps nearby. The bridge lies on top of a lot of river huts like beavers make, and the noise of the river becomes loud below it. On the other edge, across the river, I see a path go a ways off, all bright in the white light of the moon.

Paragraph 5:

I have an urge. I have an urge to walk across the bridge, to leave by the moon-white path from the valley and return here no more. My mother didn't raise me to do strange things like sit by huts with antler-headed men and girls that smell like flowers. I'm one of the nomadic people, and am made for walking. I want to rise up out of this valley, where everything's wet and rotten-smelling. A village by the river, where the shagfoal walk. There's no good in it.

Paragraph 6:

Yet I think now of a lot of things. If I walk all alone and don't find anything to eat, I'll go hungry, like before I came to the white-skin hut. I think of the girl, with the strip of ox-fur holding back her long bright hair, and the smell of flowers all around her and the many good things she says. I think about Hob's son, whom I want to hear about, and now I look at the bridge and the white path across it, and hear the loud noise of the river, falling there in the dark.

Page 28, Paragraph 1 (first full paragraph):

I take a piss against the tree, and turn, and go back by the river's edge, and through the reeds, up the dirt rise and around the white skin hut, where I come by the pigpen. I crawl in the branch hut and beneath the hay. I shut my eyes, so that all of the world goes from me.

Tuesday, September 15, 2009

Page 26, Paragraph 6; Page 27, Paragraphs 1 - 3

Page 26, Paragraph 6:

I think about how one may say something that isn't so; and more, on all a man can do with thoughts like this - they're that big. I think about how a long strange saying is like a path on which a man can journey all over the world. The girl has put so many strange thoughts in my belly that there's no peace in me.* I turn this way and that on the hay, and now I need to take a piss.

Page 27, Paragraph 1 (first full paragraph):

I can't piss by the white-skin hut, where Hob might smell me. I crawl out of the branch hut to stand up and cross the pigpen. I go out by the hole in the wall, and now I walk quietly in front of the hut where there's a little hill of branches and briar; the girl and Hob have foraged a lot of firewood and put it here. Now I go around the edge of the stick hill and come by the edge of the dirt rise.

Paragraph 2:

There in the sky above me the sky-beasts have all pulled back, one from another, and behind them is the moon. By its light I see the reeds standing all sharp and white, so I can see where the grass is tramped down all flat, like the path that the girl takes to the river to get water. Now I come down off the rise and onto a dry path free of mud that I can walk on.

Paragraph 3:

My leg doesn't hurt - it's getting better. I look down at it. The leaf that the girl put below my knee is still there, held to my leg with mud. This is good. I walk on and going this way come to where the slow, dark river moves between the trees - I go there, too. I didn't think I'd have to walk this far to piss, but it's good for me to walk instead of lying in the pigpen.

*You can imagine a lot of similar thoughts going through Adam's head after he ate the fruit of the tree of knowledge, can't you?

I think about how one may say something that isn't so; and more, on all a man can do with thoughts like this - they're that big. I think about how a long strange saying is like a path on which a man can journey all over the world. The girl has put so many strange thoughts in my belly that there's no peace in me.* I turn this way and that on the hay, and now I need to take a piss.

Page 27, Paragraph 1 (first full paragraph):

I can't piss by the white-skin hut, where Hob might smell me. I crawl out of the branch hut to stand up and cross the pigpen. I go out by the hole in the wall, and now I walk quietly in front of the hut where there's a little hill of branches and briar; the girl and Hob have foraged a lot of firewood and put it here. Now I go around the edge of the stick hill and come by the edge of the dirt rise.

Paragraph 2:

There in the sky above me the sky-beasts have all pulled back, one from another, and behind them is the moon. By its light I see the reeds standing all sharp and white, so I can see where the grass is tramped down all flat, like the path that the girl takes to the river to get water. Now I come down off the rise and onto a dry path free of mud that I can walk on.

Paragraph 3:

My leg doesn't hurt - it's getting better. I look down at it. The leaf that the girl put below my knee is still there, held to my leg with mud. This is good. I walk on and going this way come to where the slow, dark river moves between the trees - I go there, too. I didn't think I'd have to walk this far to piss, but it's good for me to walk instead of lying in the pigpen.

*You can imagine a lot of similar thoughts going through Adam's head after he ate the fruit of the tree of knowledge, can't you?

Page 26, Paragraphs 2 - 5

Page 26, Paragraph 2:

Now there's a loud noise coming from the white-skin hut, across from the pigpen here - it's Hob. He yells, "Where's that girl? Is that a girl making noise behind my hut?" and so forth. The girl jumps up and says quietly, "I'm going to go a ways away so that Hob doesn't find me - and find you, too, while he's at it." She starts to walk off through the hay, enclosed in the smell of flowers. "Hold on," I whisper, because I'm afraid that Hob may hear. I say, "You didn't talk about Hob's son or how he went away like I wanted to know."

Paragraph 3:

"It's a long story," she says, "longer than I can tell you all at once. At dawn Hob is going off - when that happens I'll come back here and tell you more about Hob's son." Now she bends down and licks my cheek.

Paragraph 4:

She stands up, and turns, and she leaves quick as a deer, through the entry, around the pigpen, off into the darkness. I can't see her anymore. Her flower-smell is taken by the wind, as if the wind wants no one else to smell it, only him. Beneath my belly, I have an erection, against which the hay prickles sharply. Her spit becomes cold on my cheek.

Paragraph 5:

Whispers come from the white-skin hut: the man to the girl and the girl back to the man, and now all is quiet. Her flower-smell has all gone away, so I can smell more of the pig that used to be here. I smell a rotten tree with its stump full of stagnant water, and I smell the slow river, moving far away. Now I turn so I'm facing up, with my back to the hay, looking up to the sky. There's nothing in the sky but darkness.

Now there's a loud noise coming from the white-skin hut, across from the pigpen here - it's Hob. He yells, "Where's that girl? Is that a girl making noise behind my hut?" and so forth. The girl jumps up and says quietly, "I'm going to go a ways away so that Hob doesn't find me - and find you, too, while he's at it." She starts to walk off through the hay, enclosed in the smell of flowers. "Hold on," I whisper, because I'm afraid that Hob may hear. I say, "You didn't talk about Hob's son or how he went away like I wanted to know."

Paragraph 3:

"It's a long story," she says, "longer than I can tell you all at once. At dawn Hob is going off - when that happens I'll come back here and tell you more about Hob's son." Now she bends down and licks my cheek.

Paragraph 4:

She stands up, and turns, and she leaves quick as a deer, through the entry, around the pigpen, off into the darkness. I can't see her anymore. Her flower-smell is taken by the wind, as if the wind wants no one else to smell it, only him. Beneath my belly, I have an erection, against which the hay prickles sharply. Her spit becomes cold on my cheek.

Paragraph 5:

Whispers come from the white-skin hut: the man to the girl and the girl back to the man, and now all is quiet. Her flower-smell has all gone away, so I can smell more of the pig that used to be here. I smell a rotten tree with its stump full of stagnant water, and I smell the slow river, moving far away. Now I turn so I'm facing up, with my back to the hay, looking up to the sky. There's nothing in the sky but darkness.

Monday, September 14, 2009

Page 26, Paragraph 1; Note

Back at it.

***

Page 26 (the one with the lovely Jose Villarrubia illustration on the facing page), Paragraph 1:

Here she says no more, but sits up and takes a breath. Now she softly makes a noise that has words in it, yet it's better than anything I've ever heard before, except from birds. The words she uses are like this*:

*I've tried to preserve the rhyme scheme of the original, but the meter's kind of fucked, I'm afraid.

***

Page 26 (the one with the lovely Jose Villarrubia illustration on the facing page), Paragraph 1:

Here she says no more, but sits up and takes a breath. Now she softly makes a noise that has words in it, yet it's better than anything I've ever heard before, except from birds. The words she uses are like this*:

It puts a chill in my belly to hear her. Now she's quiet and says no more, but I can still hear her song, because it goes around and around, like a bird with a broken wing, in my head. Up the valley's edge, in the shadow of the tree...Oh, how may I find a mate, the journey-boy says

Up the valley's edge, in the shadow of the tree, by the earthworm's hill and all

And lie with her before I'm put to dirt all grey

Up the valley's edge, in the shadow of the tree

By the earthworm's hill and the river's knee

And there they lie, he and she, beneath the grass and all

*I've tried to preserve the rhyme scheme of the original, but the meter's kind of fucked, I'm afraid.

Friday, September 11, 2009

Off-Topic: In Memoriam - September 11, 2001

I always think of this song today. There are a lot of great covers of it, but Dylan's original remains my favorite.

"There must be some way out of here," said the joker to the thief,

"There's too much confusion, I can't get no relief.

Businessmen, they drink my wine, plowmen dig my earth,

None of them along the line know what any of it is worth."

"No reason to get excited," the thief, he kindly spoke,

"There are many here among us who feel that life is but a joke.

But you and I, we've been through that, and this is not our fate,

So let us not talk falsely now, the hour is getting late."

All along the watchtower, princes kept the view

While all the women came and went, barefoot servants, too.

Outside in the distance a wildcat did growl,

Two riders were approaching, the wind began to howl.

Copyright ©1968; renewed 1996 Dwarf Music

"There must be some way out of here," said the joker to the thief,

"There's too much confusion, I can't get no relief.

Businessmen, they drink my wine, plowmen dig my earth,

None of them along the line know what any of it is worth."

"No reason to get excited," the thief, he kindly spoke,

"There are many here among us who feel that life is but a joke.

But you and I, we've been through that, and this is not our fate,

So let us not talk falsely now, the hour is getting late."

All along the watchtower, princes kept the view

While all the women came and went, barefoot servants, too.

Outside in the distance a wildcat did growl,

Two riders were approaching, the wind began to howl.

Copyright ©1968; renewed 1996 Dwarf Music

Thursday, September 10, 2009

Page 25, Paragraphs 2 - 5

Wow, this was really challenging - it took me almost an hour to figure out this one little passage.

***

Page 25, Paragraph 2:

"Why, if a path like this is made," she says, "even more good times will come by the village here than will come to other villages, because the river bridge is here - journeying men have no way to go other than to come by here, and many good times will come here with them."

Paragraph 3:

I turn onto my belly now, with the hay prickling my penis. I lie with my ass and legs in the little branch-hut and my head and arms outside of it. I turn my head to look into the sky, where I can tell that the sky-beasts have all shut their eyes because I don't see any lights. I think about the path that the girl's been talking about, but I can't really picture it fully. I say to the girl, "How would the path be made if a lot of people don't walk by it? How can people walk along this path if they don't know the way?"

Paragraph 4:

Now her talk becomes strange and hard to understand. "There's a way that a man can know of the path even if the path is so long that it goes all over the world, and the way of it is this," she says. "In all of their many villages, there are antler-headed men that make a strange and long description that tells of many things. It tells of the village where the antler-headed man is, and tells of the hills and routes nearby, so that people who come from other places can find a way to him. Now all the many descriptions by the many antler-headed men are set in a line, to make one big description even bigger than them, that tells of the way from the southern coast to the northern forest."

Paragraph 5:

"Why, how is this?" I say. "If a description is that long, a man can't understand it all at once!" "Ah," she says now, "this is where the strange part comes. The antler- headed men make their long description in such a way that a man can hear it one or two times and then know it forever. The saying of it is made with noises that are like each other, that is, in a form of speaking that is unlike any other, so you can remember it better."

***

That's the most complex explanation of a song I've ever heard!

***

Page 25, Paragraph 2:

"Why, if a path like this is made," she says, "even more good times will come by the village here than will come to other villages, because the river bridge is here - journeying men have no way to go other than to come by here, and many good times will come here with them."

Paragraph 3:

I turn onto my belly now, with the hay prickling my penis. I lie with my ass and legs in the little branch-hut and my head and arms outside of it. I turn my head to look into the sky, where I can tell that the sky-beasts have all shut their eyes because I don't see any lights. I think about the path that the girl's been talking about, but I can't really picture it fully. I say to the girl, "How would the path be made if a lot of people don't walk by it? How can people walk along this path if they don't know the way?"

Paragraph 4:

Now her talk becomes strange and hard to understand. "There's a way that a man can know of the path even if the path is so long that it goes all over the world, and the way of it is this," she says. "In all of their many villages, there are antler-headed men that make a strange and long description that tells of many things. It tells of the village where the antler-headed man is, and tells of the hills and routes nearby, so that people who come from other places can find a way to him. Now all the many descriptions by the many antler-headed men are set in a line, to make one big description even bigger than them, that tells of the way from the southern coast to the northern forest."

Paragraph 5:

"Why, how is this?" I say. "If a description is that long, a man can't understand it all at once!" "Ah," she says now, "this is where the strange part comes. The antler- headed men make their long description in such a way that a man can hear it one or two times and then know it forever. The saying of it is made with noises that are like each other, that is, in a form of speaking that is unlike any other, so you can remember it better."

***

That's the most complex explanation of a song I've ever heard!

Wednesday, September 9, 2009

Off-Topic: 1001 Books You Must Read Before You Die

As you may be noticing, I'm slightly obsessed with lists, especially those involving the arts. I recently came across the list of books in Peter Boxall's 1001 Books You Must Read Before You Die and checked to see how many I've read; I performed pitifully, having only read sixty-one of the books on the list, or only about 6% of the titles on the list.

Anyway, here's the ones I have read:

Get Shorty – Elmore Leonard

Watchmen – Alan Moore & David Gibbons (suprise!)

The Handmaid’s Tale – Margaret Atwood

The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy – Douglas Adams

The World According to Garp – John Irving

The Shining – Stephen King

Song of Solomon – Toni Morrison

Interview With the Vampire – Anne Rice

Slaughterhouse-five – Kurt Vonnegut, Jr.

The Godfather – Mario Puzo

2001: A Space Odyssey – Arthur C. Clarke

The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test – Tom Wolfe

One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich – Aleksandr Isayevich Solzhenitsyn

One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest – Ken Kesey

A Clockwork Orange – Anthony Burgess

Stranger in a Strange Land – Robert Heinlein

Catch-22 – Joseph Heller

To Kill a Mockingbird – Harper Lee

On the Road – Jack Kerouac

Seize the Day – Saul Bellow

The Lord of the Rings – J.R.R. Tolkien

The Last Temptation of Christ – Nikos Kazantzákis

Lord of the Flies – William Golding

The Old Man and the Sea – Ernest Hemingway

The Catcher in the Rye – J.D. Salinger

Nineteen Eighty-Four – George Orwell

Animal Farm – George Orwell

Native Son – Richard Wright

The Grapes of Wrath – John Steinbeck

The Hobbit – J.R.R. Tolkien

Keep the Aspidistra Flying – George Orwell

At the Mountains of Madness – H.P. Lovecraft

Brave New World – Aldous Huxley

The Thin Man – Dashiell Hammett

The Maltese Falcon – Dashiell Hammett

A Farewell to Arms – Ernest Hemingway

Red Harvest – Dashiell Hammett

All Quiet on the Western Front – Erich Maria Remarque

The Sound and the Fury – William Faulkner

The Sun Also Rises – Ernest Hemingway

The Great Gatsby – F. Scott Fitzgerald

A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man – James Joyce

Tarzan of the Apes – Edgar Rice Burroughs

Howards End – E.M. Forster

Heart of Darkness – Joseph Conrad

The Awakening – Kate Chopin

Dracula – Bram Stoker

The Yellow Wallpaper – Charlotte Perkins Gilman

The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde – Robert Louis Stevenson

Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland – Lewis Carroll

Great Expectations – Charles Dickens

The Blithedale Romance – Nathaniel Hawthorne

Moby-Dick – Herman Melville

Wuthering Heights – Emily Brontë

The Purloined Letter – Edgar Allan Poe

The Pit and the Pendulum – Edgar Allan Poe

The Fall of the House of Usher – Edgar Allan Poe

Frankenstein – Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley

Emma – Jane Austen

A Modest Proposal – Jonathan Swift

Moll Flanders – Daniel Defoe

Here's a link to the entire list, if you want to check it out.

Anyway, here's the ones I have read:

Get Shorty – Elmore Leonard

Watchmen – Alan Moore & David Gibbons (suprise!)

The Handmaid’s Tale – Margaret Atwood

The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy – Douglas Adams

The World According to Garp – John Irving

The Shining – Stephen King

Song of Solomon – Toni Morrison

Interview With the Vampire – Anne Rice

Slaughterhouse-five – Kurt Vonnegut, Jr.

The Godfather – Mario Puzo

2001: A Space Odyssey – Arthur C. Clarke

The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test – Tom Wolfe

One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich – Aleksandr Isayevich Solzhenitsyn

One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest – Ken Kesey

A Clockwork Orange – Anthony Burgess

Stranger in a Strange Land – Robert Heinlein

Catch-22 – Joseph Heller

To Kill a Mockingbird – Harper Lee

On the Road – Jack Kerouac

Seize the Day – Saul Bellow

The Lord of the Rings – J.R.R. Tolkien

The Last Temptation of Christ – Nikos Kazantzákis

Lord of the Flies – William Golding

The Old Man and the Sea – Ernest Hemingway

The Catcher in the Rye – J.D. Salinger

Nineteen Eighty-Four – George Orwell

Animal Farm – George Orwell

Native Son – Richard Wright

The Grapes of Wrath – John Steinbeck

The Hobbit – J.R.R. Tolkien

Keep the Aspidistra Flying – George Orwell

At the Mountains of Madness – H.P. Lovecraft

Brave New World – Aldous Huxley

The Thin Man – Dashiell Hammett

The Maltese Falcon – Dashiell Hammett

A Farewell to Arms – Ernest Hemingway

Red Harvest – Dashiell Hammett

All Quiet on the Western Front – Erich Maria Remarque

The Sound and the Fury – William Faulkner

The Sun Also Rises – Ernest Hemingway

The Great Gatsby – F. Scott Fitzgerald

A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man – James Joyce

Tarzan of the Apes – Edgar Rice Burroughs

Howards End – E.M. Forster

Heart of Darkness – Joseph Conrad

The Awakening – Kate Chopin

Dracula – Bram Stoker

The Yellow Wallpaper – Charlotte Perkins Gilman

The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde – Robert Louis Stevenson

Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland – Lewis Carroll

Great Expectations – Charles Dickens

The Blithedale Romance – Nathaniel Hawthorne

Moby-Dick – Herman Melville

Wuthering Heights – Emily Brontë

The Purloined Letter – Edgar Allan Poe

The Pit and the Pendulum – Edgar Allan Poe

The Fall of the House of Usher – Edgar Allan Poe

Frankenstein – Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley

Emma – Jane Austen

A Modest Proposal – Jonathan Swift

Moll Flanders – Daniel Defoe

Here's a link to the entire list, if you want to check it out.

Page 24, Paragraphs 6 - 8; Page 25, Paragraph 1

Page 24, Paragraph 6:

She says, "Hob was here with his son by the river for a long time, where the settlers come so Hob can counsel them and do a lot of things for them. For all he does, the settlers find skins and food and many things for Hob, as is his due."

Paragraph 7:

"Of all the things there are for Hob to do," she says, "there's one thing that's bigger than the others." She says, "There are many villages across the world, from sea to sea, and all of them have antler-headed men like Hob. The antler-headed men all come together in one place, to talk and to counsel one another, after which they all talk about a big task that they've thought of together. I sit the other way around in the grass - I'm glad I can hear this."

Paragraph 8:

She says, "The antler-headed men's plan is to make a path, bigger than any path that's ever been made, which goes from the sea in the south to the forest in the north. The path is to run by the hills and the high places, and by the valley's edge."

Page 25, Paragraph 1:

This is a longer distance than I can imagine, because I've never seen the sea - I've only heard of it. "How would it be good to make this big path?" I say to her, as she sits in the dark and plays with her hair. She says, "The path would be there for many people's travels, so that people from one village could journey to another village far away and take stones and hides with them and trade them for things from the other villages. This way, all villages will have things they haven't had before, and good times will come to everyone that lives along this path."

She says, "Hob was here with his son by the river for a long time, where the settlers come so Hob can counsel them and do a lot of things for them. For all he does, the settlers find skins and food and many things for Hob, as is his due."

Paragraph 7:

"Of all the things there are for Hob to do," she says, "there's one thing that's bigger than the others." She says, "There are many villages across the world, from sea to sea, and all of them have antler-headed men like Hob. The antler-headed men all come together in one place, to talk and to counsel one another, after which they all talk about a big task that they've thought of together. I sit the other way around in the grass - I'm glad I can hear this."

Paragraph 8:

She says, "The antler-headed men's plan is to make a path, bigger than any path that's ever been made, which goes from the sea in the south to the forest in the north. The path is to run by the hills and the high places, and by the valley's edge."

Page 25, Paragraph 1:

This is a longer distance than I can imagine, because I've never seen the sea - I've only heard of it. "How would it be good to make this big path?" I say to her, as she sits in the dark and plays with her hair. She says, "The path would be there for many people's travels, so that people from one village could journey to another village far away and take stones and hides with them and trade them for things from the other villages. This way, all villages will have things they haven't had before, and good times will come to everyone that lives along this path."

Tuesday, September 8, 2009

Page 24, Paragraphs 2 - 5

Page 24, Paragraph 2:

I hear the noise of doors moving in the entryway, and I smell flowers, and that's good. The girl comes into the pigpen and comes across to the little hut where I'm sitting. I start to say a lot of things to her, but she puts her hand to my mouth, and signs for me to be quiet. Now she whispers like the sound the wind makes in the reeds.

Paragraph 3:

She says quietly, "I've come with food for you." Out of her wrap she now takes cooked meat and a food that I don't recognize that's hard on the outside and soft on the inside. I take this from her to eat, and say, "How is this hard and soft?"

Paragraph 4:

She hisses, as if to say I'm louder than I need to be. She says, "That food is made in the fire from wheat flour made from the wheat that grows nearby, with a little water mixed in." I eat it, and it's good, and the cooked meat's good in my mouth. It tastes like ox. She sits silently on her knees by me. My mouth's empty now, and I can't think of anything to say to her except about Hob's son, and how it is that he's not here anymore.

Paragraph 5:

She looks at me, and the bats fly in circles through the sky above the pigpen. A quiet time goes by, and now in the dark she says, "Ah, it's a long story, and there's no good in it." Now she's quiet, so I think she's not going to say anything else. I'm wrong.

***

EDIT: I forgot to type in the last couple of sentences of paragraph 5 when I first posted this. Sorry - it's corrected now.

I hear the noise of doors moving in the entryway, and I smell flowers, and that's good. The girl comes into the pigpen and comes across to the little hut where I'm sitting. I start to say a lot of things to her, but she puts her hand to my mouth, and signs for me to be quiet. Now she whispers like the sound the wind makes in the reeds.

Paragraph 3:

She says quietly, "I've come with food for you." Out of her wrap she now takes cooked meat and a food that I don't recognize that's hard on the outside and soft on the inside. I take this from her to eat, and say, "How is this hard and soft?"

Paragraph 4:

She hisses, as if to say I'm louder than I need to be. She says, "That food is made in the fire from wheat flour made from the wheat that grows nearby, with a little water mixed in." I eat it, and it's good, and the cooked meat's good in my mouth. It tastes like ox. She sits silently on her knees by me. My mouth's empty now, and I can't think of anything to say to her except about Hob's son, and how it is that he's not here anymore.

Paragraph 5:

She looks at me, and the bats fly in circles through the sky above the pigpen. A quiet time goes by, and now in the dark she says, "Ah, it's a long story, and there's no good in it." Now she's quiet, so I think she's not going to say anything else. I'm wrong.

***

EDIT: I forgot to type in the last couple of sentences of paragraph 5 when I first posted this. Sorry - it's corrected now.

Monday, September 7, 2009

Page 23, Paragraph 6 - 8; Page 24, Paragraph 1

It's Labor Day - give your favorite union member a hug.

***

Page 23, Paragraph 6:

I crawl in the little branch-hut now and dig underneath the hay. I put the jerky in my mouth to chew; my belly feels good. My walk from the thicket of trees has made me weak, and now I lie with my cheek to the prickling grass, and suck on the meat, and close my eyes.

Paragraph 7 (first paragraph after the break):

Now I open them. Everything's dark. Something's in my mouth. Why, it's the jerky stick. The end of it has become soft, like shit, and the taste of meat is thick on my tongue. Something's prickling my cheek, yet I remember flowers, and the girl, and the hut, and the pigpen that stands by it, and I remember the way I came here.

Paragraph 8:

There across from the pigpen stands the white-skin hut - from there I hear a man saying many things and a girl speaking back to him. I think Hob's come back here from what he was doing with the settlers.

Page 24, Paragraph 1:

Now everything gets quiet. I sit in the hay, chewing on the jerky - some time goes by like this.

***

I'm now 20 pages into this chapter - woo-hoo!

***

Page 23, Paragraph 6:

I crawl in the little branch-hut now and dig underneath the hay. I put the jerky in my mouth to chew; my belly feels good. My walk from the thicket of trees has made me weak, and now I lie with my cheek to the prickling grass, and suck on the meat, and close my eyes.

Paragraph 7 (first paragraph after the break):

Now I open them. Everything's dark. Something's in my mouth. Why, it's the jerky stick. The end of it has become soft, like shit, and the taste of meat is thick on my tongue. Something's prickling my cheek, yet I remember flowers, and the girl, and the hut, and the pigpen that stands by it, and I remember the way I came here.

Paragraph 8:

There across from the pigpen stands the white-skin hut - from there I hear a man saying many things and a girl speaking back to him. I think Hob's come back here from what he was doing with the settlers.

Page 24, Paragraph 1:

Now everything gets quiet. I sit in the hay, chewing on the jerky - some time goes by like this.

***

I'm now 20 pages into this chapter - woo-hoo!

Sunday, September 6, 2009

Off-Topic: Annoyance; Newsweek List

This is extremely irritating.

I saved a blog entry I had started back on 8/19, and completed it just now, and instead of posting at the top of the front page of my blog, it posted back by my 8/19 post.

Here's the post, if anyone wants to read it - it's about Newsweek's Top 100 Books list.

Does anyone know how I can prevent this from happening again in the future?

I saved a blog entry I had started back on 8/19, and completed it just now, and instead of posting at the top of the front page of my blog, it posted back by my 8/19 post.

Here's the post, if anyone wants to read it - it's about Newsweek's Top 100 Books list.

Does anyone know how I can prevent this from happening again in the future?

Labels:

links,

lists,

off-topic,

other authors,

the internets

Page 23, Paragraph 2 - 5

I read ahead to about page 32 last night - it definitely gets even more interesting and mythic as it goes along.

***

Page 23, Paragraph 2:

The dirt walls of the pen come up to my neck; the wall has an entryway with a wooden door. The dirt floor of the pigpen is all covered up with hay, thick and warm, and in the corner stands a little hut made of branches. I can't smell much of a pig odor here, because I mostly smell flowers. The girl opens the door and we go into the pigpen.

Paragraph 3:

"Hob's not going to look in here," she says, "now that the pig's no longer here." She says, "If you hide in the hay, I'll go do work for Hob, after which I'll come back at night with food for you." Now she puts in my hand another stick of jerky to eat until she comes back, and now she opens the door to go out. I want her to stay longer. I try to think of something to say to her so she won't leave so fast.

Paragraph 4:

I say, "How is it that you say Hob doesn't have a son anymore? Did his son go the way the pig that used to stay in this pen went?"

Paragraph 5:

At this she looks down; a dark look comes over her face. "Hob's son doesn't come here anymore," she says, and then says, "I'm going now." She leaves and shuts

the door behind her. She walks around the hut so I can't see her anymore, but I smell her, like flowers falling off trees.

***

Page 23, Paragraph 2:

The dirt walls of the pen come up to my neck; the wall has an entryway with a wooden door. The dirt floor of the pigpen is all covered up with hay, thick and warm, and in the corner stands a little hut made of branches. I can't smell much of a pig odor here, because I mostly smell flowers. The girl opens the door and we go into the pigpen.

Paragraph 3:

"Hob's not going to look in here," she says, "now that the pig's no longer here." She says, "If you hide in the hay, I'll go do work for Hob, after which I'll come back at night with food for you." Now she puts in my hand another stick of jerky to eat until she comes back, and now she opens the door to go out. I want her to stay longer. I try to think of something to say to her so she won't leave so fast.

Paragraph 4:

I say, "How is it that you say Hob doesn't have a son anymore? Did his son go the way the pig that used to stay in this pen went?"

Paragraph 5:

At this she looks down; a dark look comes over her face. "Hob's son doesn't come here anymore," she says, and then says, "I'm going now." She leaves and shuts

the door behind her. She walks around the hut so I can't see her anymore, but I smell her, like flowers falling off trees.

Saturday, September 5, 2009

Page 22, Paragraphs 8 -10; Page 23, Paragraph 1

Page 22, Paragraph 8:

Her smile becomes wider at this, and she says, "It's good for me to find someone like you, that thinks and speaks strangely. Come on - you don't have time to think about this. Come across the reeds and by the white-skin hut so you can hide in the building there."

Paragraph 9:

She stands and takes my hand - her hand is little now, and warm. "Come now," she says, and pulls, and this way she helps me stand. I don't have any strength, and she puts her arm around my back to help me walk. It smells like I'm walking bent over with my face in flowers.

Paragraph 10:

We come down slowly off where the thicket of trees is and now we walk through the reeds, where there's a dry path between the water and the mud. The path goes by the dirt rise where the white-skin hut stands, and now we walk up the rise, her arm around my back, and come by the hut. We've only walked a little way, but the strength has gone from me; my legs are shaking.

Page 23, Paragraph 1:

Seen from here, the hut is bigger than I thought, though it's made for only one man and one girl. For the first time I understand how it is with Hob, being the boss over many people. Times are good for him. Hopefully, times will become this good for me.* The girl pulls my hand, and we walk like this around the hut until we come to the pigpen.

*Jeez - even in 4,000 BC, people were jealous of each others' status symbols.

Her smile becomes wider at this, and she says, "It's good for me to find someone like you, that thinks and speaks strangely. Come on - you don't have time to think about this. Come across the reeds and by the white-skin hut so you can hide in the building there."

Paragraph 9:

She stands and takes my hand - her hand is little now, and warm. "Come now," she says, and pulls, and this way she helps me stand. I don't have any strength, and she puts her arm around my back to help me walk. It smells like I'm walking bent over with my face in flowers.

Paragraph 10:

We come down slowly off where the thicket of trees is and now we walk through the reeds, where there's a dry path between the water and the mud. The path goes by the dirt rise where the white-skin hut stands, and now we walk up the rise, her arm around my back, and come by the hut. We've only walked a little way, but the strength has gone from me; my legs are shaking.

Page 23, Paragraph 1:

Seen from here, the hut is bigger than I thought, though it's made for only one man and one girl. For the first time I understand how it is with Hob, being the boss over many people. Times are good for him. Hopefully, times will become this good for me.* The girl pulls my hand, and we walk like this around the hut until we come to the pigpen.

*Jeez - even in 4,000 BC, people were jealous of each others' status symbols.

Friday, September 4, 2009

Monkeyin' Around With Google Books

I gotta see if this works. This is the Google Books preview of Alan Moore: Comics As Performance, Fiction As Scalpel By Annalisa Di Liddo. I found it while I was doing a bit of research on Mr. Moore's literary influences (the inspiration for this month's poll, in case you haven't guessed).

Sweet. I never realized you can embed entire books from Google Books in your blog. I'll have to be careful - I'll have the entire bloody Library of Congress here if I don't look out. :)

Sweet. I never realized you can embed entire books from Google Books in your blog. I'll have to be careful - I'll have the entire bloody Library of Congress here if I don't look out. :)

Labels:

links,

other authors,

the internets,

words from The Man

Page 22, Paragraphs 2 - 7

Page 22, Paragraph 2:

This makes me frightened. I think of his black face, his sticks like the horns of an animal, and say, "It'd be good for me to journey on, so that he doesn't find me." I try to stand up now, but there isn't much strength in me.

Paragraph 3:

She frowns even bigger and says, "Your leg hasn't had time to get better, and you haven't ate enough." She's right. She says, "You can hide where Hob won't find you - where only I'll know where you are. Behind the hut," she says, "there's a dirt building wall for a pigpen. Hob doesn't have the pig anymore - the building's empty, so you can hide in it." I realize this is the building I saw by the light of the fire.

Paragraph 4:

"You can stay there," she says, "while your leg's getting better, and I'll find food for you. If Hob sees that more food's gone, why, I'll tell him that the food was taken by a rat."

Paragraph 5:

This is something stranger than I can understand. I think about it this way and that, but I can't understand it correctly. "How is it," I say now, "that I change into a rat?"

Paragraph 6:

She smiles at this, and says, "You're not going to change into a rat. I'm just going to be saying that to Hob." I look at her. I still don't understand what she's saying, and seeing this makes her smile bigger. "Why," she says now, "don't you understand that you can say something that isn't so?"

Paragraph 7:

This is an idea that I've never heard of - that you can say something that isn't so. It's a bigger thought than I can hold in my mind all at one time. I look at her with my mouth hanging open. I shake my head and make the sign for "no".

***

This stuff is not actually as silly as it sounds - lying creates cognitive dissonance, which in turn create negative emotions which make it difficult to think - so essentially we're hard-wired to tell the truth. (Yes, I know that makes politicians even more difficult to understand than they already are.)

This makes me frightened. I think of his black face, his sticks like the horns of an animal, and say, "It'd be good for me to journey on, so that he doesn't find me." I try to stand up now, but there isn't much strength in me.

Paragraph 3:

She frowns even bigger and says, "Your leg hasn't had time to get better, and you haven't ate enough." She's right. She says, "You can hide where Hob won't find you - where only I'll know where you are. Behind the hut," she says, "there's a dirt building wall for a pigpen. Hob doesn't have the pig anymore - the building's empty, so you can hide in it." I realize this is the building I saw by the light of the fire.

Paragraph 4:

"You can stay there," she says, "while your leg's getting better, and I'll find food for you. If Hob sees that more food's gone, why, I'll tell him that the food was taken by a rat."

Paragraph 5:

This is something stranger than I can understand. I think about it this way and that, but I can't understand it correctly. "How is it," I say now, "that I change into a rat?"

Paragraph 6:

She smiles at this, and says, "You're not going to change into a rat. I'm just going to be saying that to Hob." I look at her. I still don't understand what she's saying, and seeing this makes her smile bigger. "Why," she says now, "don't you understand that you can say something that isn't so?"

Paragraph 7:

This is an idea that I've never heard of - that you can say something that isn't so. It's a bigger thought than I can hold in my mind all at one time. I look at her with my mouth hanging open. I shake my head and make the sign for "no".

***

This stuff is not actually as silly as it sounds - lying creates cognitive dissonance, which in turn create negative emotions which make it difficult to think - so essentially we're hard-wired to tell the truth. (Yes, I know that makes politicians even more difficult to understand than they already are.)

Thursday, September 3, 2009

Page 21, Paragraphs 6 - 9; Page 22, Paragraph 1

Wow - I see I've already gotten as many responses on my new poll in 3 days as I did on the last one in a month. That's wonderful - keep the votes (and comments, and other feedback) coming, folks.

***

Page 21, Paragraph 6:

The skin on her face is soft, but she has little scratch-marks on her cheek. A butterfly flies all around her hair, and now it sits on the strip of white fur wrapped around her head. "How did you come to be with Hob," I say, "if he's dark and isn't well?"

Paragraph 7:

She sighs and says, "I come from a far-away place, and have been made to work for Hob. Hob has say over many settlers, for he is a..."

Paragraph 8:

Here she says something I don't understand. I say, "How's that?" She says, "It's like a wise man [or shaman], but stranger."

Paragraph 9:

"Hob no longer has a son to work for him on his big makings," she says now, "which is how I was made to come and work for him, and cook his food, and find wood for him, and so forth." She frowns when she says this. The lowing of an aurochs comes from way up and the reeds around the hut are grey and move like smoke in the wind. "Where is Hob now?" I say.

Page 22, Paragraph 1:

"Before sunrise he walked off," she says, "to journey to the settlers downriver there. He has many things to do, after which he's coming back here."

***

This is about as far as I've ever got in this book, by the way, so I'll be headed into terra incognita here soon.

***

Page 21, Paragraph 6:

The skin on her face is soft, but she has little scratch-marks on her cheek. A butterfly flies all around her hair, and now it sits on the strip of white fur wrapped around her head. "How did you come to be with Hob," I say, "if he's dark and isn't well?"

Paragraph 7:

She sighs and says, "I come from a far-away place, and have been made to work for Hob. Hob has say over many settlers, for he is a..."

Paragraph 8:

Here she says something I don't understand. I say, "How's that?" She says, "It's like a wise man [or shaman], but stranger."

Paragraph 9:

"Hob no longer has a son to work for him on his big makings," she says now, "which is how I was made to come and work for him, and cook his food, and find wood for him, and so forth." She frowns when she says this. The lowing of an aurochs comes from way up and the reeds around the hut are grey and move like smoke in the wind. "Where is Hob now?" I say.

Page 22, Paragraph 1:

"Before sunrise he walked off," she says, "to journey to the settlers downriver there. He has many things to do, after which he's coming back here."

***

This is about as far as I've ever got in this book, by the way, so I'll be headed into terra incognita here soon.

Wednesday, September 2, 2009

Page 21, Paragraphs 2 - 5

Page 21, Paragraph 2:

She now turns quickly to look at me. "How did you see Hob?" she says, giving me a funny look. I say, "I saw you go for river water, which Hob set by [above?] the fire, from which a whiteness came." I tell her of how I saw Hob put the whiteness on her face, after which I saw no more.

Paragraph 3:

She falls slowly, with her back to the grass, her arms across her eyes to keep the light out of them. "That white is perfume," she says, "to make me smell like flowers." I understand that I saw how the antler-headed man put flowers in the water, which became white - she said it right.

Paragraph 4:

We lie on the grass. In the sky above us, the sky-beasts are now running after the sun, not the other way around. They catch up to him and eat him - the sun is no more and the light goes from the sky. The old river is grey now, and the reeds are likewise grey. I say, "How did you find food for me and make my leg better?" Now she sits up a little as she lies there, resting on one arm and looking at me. Her bright hair falls into her eyes, where she pushes it back.

Paragraph 5:

"I'm all alone except for Hob," she says. "There hasn't been anyone for me to talk with or walk with in a long time. Hob's old, with darkness in his thoughts - he's not doing well, and doesn't talk a lot. I found milk for you and helped make your leg better so you could tell me of the many things you've seen in the world, so I'd have good things to think about when I'm alone with Hob."

She now turns quickly to look at me. "How did you see Hob?" she says, giving me a funny look. I say, "I saw you go for river water, which Hob set by [above?] the fire, from which a whiteness came." I tell her of how I saw Hob put the whiteness on her face, after which I saw no more.

Paragraph 3:

She falls slowly, with her back to the grass, her arms across her eyes to keep the light out of them. "That white is perfume," she says, "to make me smell like flowers." I understand that I saw how the antler-headed man put flowers in the water, which became white - she said it right.

Paragraph 4:

We lie on the grass. In the sky above us, the sky-beasts are now running after the sun, not the other way around. They catch up to him and eat him - the sun is no more and the light goes from the sky. The old river is grey now, and the reeds are likewise grey. I say, "How did you find food for me and make my leg better?" Now she sits up a little as she lies there, resting on one arm and looking at me. Her bright hair falls into her eyes, where she pushes it back.

Paragraph 5:

"I'm all alone except for Hob," she says. "There hasn't been anyone for me to talk with or walk with in a long time. Hob's old, with darkness in his thoughts - he's not doing well, and doesn't talk a lot. I found milk for you and helped make your leg better so you could tell me of the many things you've seen in the world, so I'd have good things to think about when I'm alone with Hob."

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)